Derek Thompson, senior editor at The Atlantic, has done some impressive research into what makes something popular—much of it outlined in his book, Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (alternately subtitled “How to Succeed in an Age of Distraction” in the paperback version of the same book).

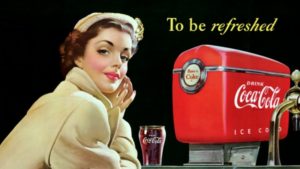

In this excerpt from his magazine, Thompson discusses the “popularity” of Raymond Loewy, widely deemed “the father of industrial design.” Loewy, featured on the cover of TIME in 1949, created the logos for Shell, Exxon, TWA, and BP, and designed the likes of the Greyhound Scenicruiser bus, Coca-Cola vending machines, the Lucky Strike cigarette package, Coldspot refrigerators, a couple of Pennsylvania railroad locomotives, and much more.

In this excerpt from his magazine, Thompson discusses the “popularity” of Raymond Loewy, widely deemed “the father of industrial design.” Loewy, featured on the cover of TIME in 1949, created the logos for Shell, Exxon, TWA, and BP, and designed the likes of the Greyhound Scenicruiser bus, Coca-Cola vending machines, the Lucky Strike cigarette package, Coldspot refrigerators, a couple of Pennsylvania railroad locomotives, and much more.

Thompson explains Loewy’s popularity: “[He] had an uncanny sense of how to make things fashionable. He believed that consumers are torn between two opposing forces: neophilia, a curiosity about new things; and neophobia, a fear of anything too new. As a result, they gravitate to products that are bold, but instantly comprehensible. Loewy called his grand theory ‘Most Advanced Yet Acceptable’—MAYA. He said to sell something surprising, make it familiar; and to sell something familiar, make it surprising.”

Thompson’s article (and book) explores an old philosophical question: Why do people like what they like? If the answers were easy, every start-up company would succeed, every marketing agency would know exactly what to do, the hit-or-miss factor would disappear. People would know exactly how to make a viral video, instead of just floating it out there and wondering if it will catch fire.

Thompson’s theories on popularity—summarized in this 50-minute video from Talks at Google—make sense, but I was struck by a new video he recorded for Big Think, piggybacking on his research about popularity.

In the video, titled “Are you cool or are you crazy?” (posted below), Thompson says:

Coolness is “a measured positive rebellion against an illegitimate mainstream, or societal norm.”

He illustrates that idea by pointing to a dress code where, in some private schools, boys have to wear coats and ties. A measured rebellion against the code would be to loosen one’s tie or unbutton your top button, moves that would generally be considered “cool” by peers (but probably not by the dean).

“But it’s not cool to go to school naked, or dressed like some weird superhero,” Thompson says, because those aren’t measured rebellions, but outright rebellions, “and that’s not considered cool.” He says the rebellion can’t be crazy or “insane” if it’s to be considered cool. Coolness, he contends, involves bending the rules as far as they’ll go without necessarily breaking them.

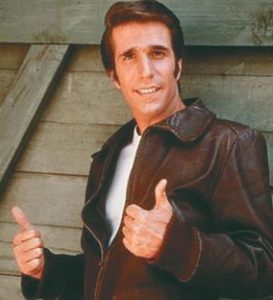

Sounds like a good start to a working definition, but at least as far back as The Fonz, kids who broke the rules were considered “cool”—by their peers, if not by the authorities. (It helped to have a leather jacket, greasy hair, a motorcycle, and absolutely the coolest thumbs-up in sitcom history.)

Sounds like a good start to a working definition, but at least as far back as The Fonz, kids who broke the rules were considered “cool”—by their peers, if not by the authorities. (It helped to have a leather jacket, greasy hair, a motorcycle, and absolutely the coolest thumbs-up in sitcom history.)

And then there are those one might say are among the “coolest” figures in U.S. history, precisely because they “broke the rules” in the process of making America great in the first place—the original settlers who rebelled against the king and the church in England; the rebels who fought the revolution and wrote the Declaration and Constitution; and anyone who has fought for civil rights and social justice ever since, including today.

Cool? Depends on how you define it. But they’re certainly heroes.

Here’s Thompson’s latest video on the definition of cool:

Meanwhile, Steven Quartz, a professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Cal Tech, literally wrote the book on cool. In this interview with MSNBC, Quartz discusses his book, Cool: How the Brain’s Hidden Quest for Cool Drives Our Economy and Shapes Our World.

And Quartz discusses the “Quest for Cool” in this WNYC podcast:

Still more cool resources:

- The Science of Cool (Mysterious Universe)

- How to be cool, according to science (The Week)

- The science behind being cool (MSNBC)

- The New Cool: Can Coolness Be Studied Like a Science? (Daily Beast)

- The hidden science behind what makes something “cool” (Rooster)

- Science of Cool (Lost in Science)

- Coolness: An Empirical Investigation (Academia)

- WonderCon 2018’s Science of Cool Panel (Pixelated Geek)

Finally, here’s James Dean, who was cool long before anybody thought about studying the science of it:

(Image at top: Shutterstock)